How To Test Throwing Code In Swift

How many times have you had to take over a project where there were unit tests, but they were hard to grasp, desperately failing, or the test target wouldn’t even build?

It is crucial to keep unit test code robust and maintainable, not to let them get abandoned and ignored over time.

At Storytel we try to make our unit tests short and readable. Due to its nature test code tends to grow long and repetitive, so it’s important to keep it clean, then working with tests doesn’t become too tedious as the project grows.

Code that throws can be tricky to test sometimes, and the resulting test code can end up ugly. In this article I will dive into different scenarios and how to solve them in nice and robust way.

XCTest is a powerful framework. In Xcode 8.3 Apple introduced few new XCTAssert functions in addition to a couple dozen existing ones. While features they provide allow to do most things a developer would desire, some things still require boilerplate code on top of natively provided features. Let’s take a look at a few cases and how to solve them.

On This Page

Verifying results of throwing functions

Functions with Equatable return types

All of existing XCTAssert functions already take throwing arguments. If the result is Equatable, a line like this will do the job:

XCTAssertEqual(try x.calculateValue(), expectedValue)

If calculateValue() throws an error, the test with fail with a message “XCTAssertEqual failed: threw error …”.

If the call did not throw and two values are not equal, the test with fail with message “XCTAssertEqual failed: a is not equal to b”, where ‘a’ and ‘b’ are descriptions of left and right arguments respectively, produced by String(describing:).

It’s quite convenient - all XCTAssert* value-checking functions verify that a call does not throw any error and returns expected result.

Functions returning Void

If a function does not return a value or if it can be ignored in the context of a test case, we can use the new XCTAssertNoThrow function that became available in Xcode 8.3:

XCTAssertNoThrow(try x.doSomething())

Interestingly enough, before Xcode 8.3 came out Storytel’s codebase had a custom function which had exact same signature, and we didn’t have to change any code except removing our custom implementation.

Functions with non-Equatable return types

Another common case is when returned type is not Equatable, or if we want to check only some properties of the returned result.

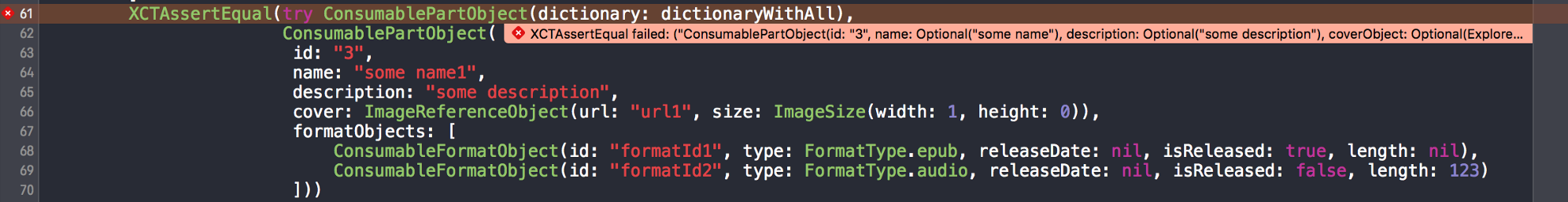

Even if the type is Equatable, equality test case failure is almost useless when object’s description is very long: it’s hard to tell which field has incorrect value:

In our projects we have a lot of functions that produce complex types that do not conform to Equatable. A common example is data model objects — we expose them as

protocols to hide internal implementation, and we don’t want them to be equatable. Each model type has a throwing initializer that takes a dictionary.

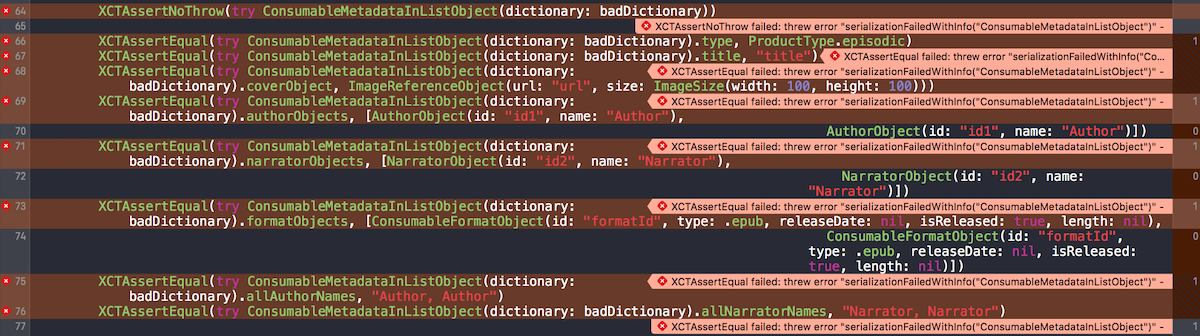

At some point we realized that our unit tests look hideous. They had repetitive code, unmeaningful optionals and when those tests were failing, boy everything was red. To make it even worse, there was lots of copy-paste. The code looked like this:

XCTAssertNoThrow(try BookObject(dictionary: sampleDictionary))

let book = try? BookObject(dictionary: sampleDictionary)

XCTAssertEqual(book?.name, "...")

XCTAssertEqual(book?.description, "...")

XCTAssertEqual(book?.rating, 5)

...

// "better" version:

XCTAssertNoThrow(try BookObject(dictionary: sampleDictionary))

XCTAssertEqual(try BookObject(dictionary: sampleDictionary).name, "...")

XCTAssertEqual(try BookObject(dictionary: sampleDictionary).description, "...")

XCTAssertEqual(try BookObject(dictionary: sampleDictionary).rating, 5)

...

When the initializer threw, it looked like many failures, even though it was really just one:

The solution turned out to be simple. The trick was to extract a result produced by XCTAssertNoThrow’s first autoclosure and to then execute additional validation closure on it, but only in case if there was a result.

public func XCTAssertNoThrow<T>(_ expression: @autoclosure () throws -> T,

_ message: String = "",

file: StaticString = #file,

line: UInt = #line,

also validateResult: (T) -> Void) {

func executeAndAssignResult(_ expression: @autoclosure () throws -> T, to: inout T?) rethrows {

to = try expression()

}

var result: T?

XCTAssertNoThrow(try executeAndAssignResult(expression, to: &result), message, file: file, line: line)

if let r = result {

validateResult(r)

}

}

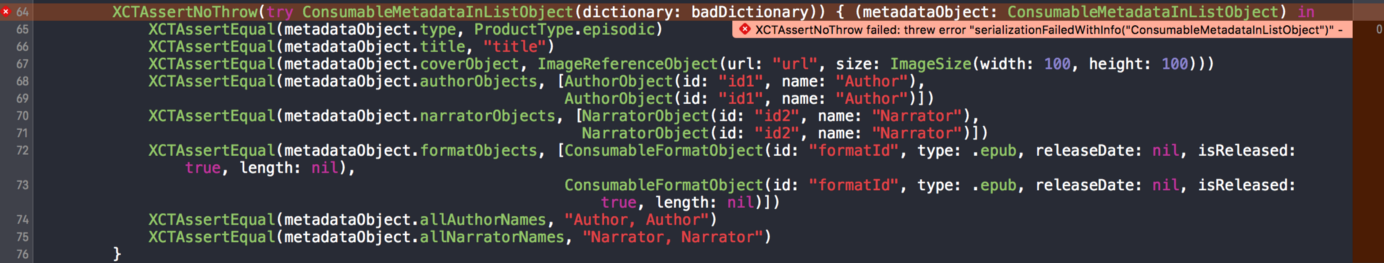

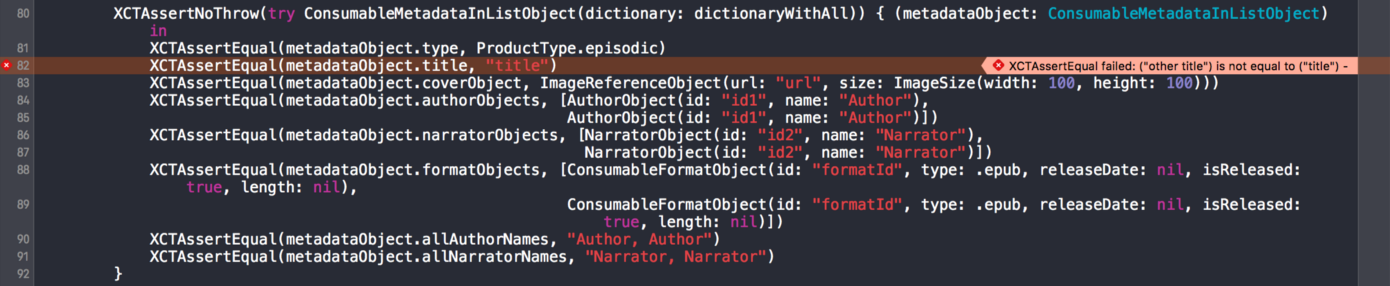

Now the same tests looked much more reasonable: readable, strongly typed and producing digestible messages.

Throwing of specific errors

In some cases we want to test the opposite — that a function does throw an error. This is often needed for testing of model deserialization.

We could already do that with existing function XCTAssertThrowsError, although if we wanted to check that some specific error was thrown, we’d have to provide a closure to evaluate the thrown error.

Looking at what kind of checks we usually had there, we noticed that it’s only two: either comparing returned error to expected one, or just checking its type. So we created two convenience functions to turn those tests into one-liners:

public func XCTAssertThrowsError<T, E: Error & Equatable>(

_ expression: @autoclosure () throws -> T,

expectedError: E,

_ message: String = "",

file: StaticString = #file,

line: UInt = #line) {

XCTAssertThrowsError(try expression(), message, file: file, line: line, { (error) in

XCTAssertNotNil(error as? E, "\(error) is not \(E.self)", file: file, line: line)

XCTAssertEqual(error as? E, expectedError, file: file, line: line)

})

}

public func XCTAssertThrowsError<T, E: Error>(

_ expression: @autoclosure () throws -> T,

expectedErrorType: E.Type,

_ message: String = "",

file: StaticString = #file,

line: UInt = #line) {

XCTAssertThrowsError(try expression(), message, file: file, line: line, { (error) in

XCTAssertNotNil(error as? E, "\(error) is not \(E.self)", file: file, line: line)

})

}

Even if it doesn’t throw…

The power of throwing functions can be used to write more robust tests for other scenarios also, where regular equality is not applicable.

Consider having an enum which cannot be made equatable — for example, if associated values of its cases are not Equatable.

Instead of using switch in test cases, we can write pure “helper” functions that throw meaningful errors.

A common example is a Result enum:

enum Result {

case success([String: Any])

case failure(Error)

}

If we were testing a function that returns Result directly, we’d have to switch over the returned value and call XCTFail in wrong cases. We would copy-paste the switch for every test case, and updating tests for new enum cases would be a nightmare.

Instead, we can create helper throwing functions to handle the enum in one place:

XCTAssert(try result.assertIsSuccess(assertValue: { (value: [String: Any]) in

XCTAssertEqual(value.count, 10)

}))

XCTAssert(try result.assertIsFailure(assertError: { (value: Error) in

XCTAssertEquals(value, MyError.case)

}))

// MARK: Helpers

private extension Result {

private enum Error: Swift.Error, CustomStringConvertible {

var message: String

var description: String { return message }

}

func assertIsSuccess(assertValue: (([String: Any]) throws -> Void)? = nil) throws -> Bool {

switch self {

case .success(let value):

try assertValue?(value)

return true

case .failure(_):

throw Error(message: "Expected .success, got .\(self)")

}

}

func assertIsFailure(assertError: ((Error) throws -> Void)? = nil) throws -> Bool {

switch self {

case .success(_):

throw Error(message: "Expected .failure, got .\(self)")

case .failure(let error):

try assertError?(value)

return true

}

}

}

This kind of approach can be used for various scenarios such as gracefully checking for optionals, which are also enums.

On creating custom assert functions

There are few things to keep in mind when writing custom test functions.

-

It’s a good practice to add line and file arguments, passing them all the way to standard

XCTAssertfunctions. This way test case failures are reported at the point where your custom assert is called, and not in the body of the function itself. -

It’s good to add

messageparameter, so the caller can provide context to the test. It’s also good to use them when writing test cases :) -

XCTFail(message:)provides a way to unconditionally fail a test, which can be very useful e.g. when testing non-equatable enums and falling through to an unexpected case.

XCTest framework has grown to be very powerful in the past year, and we try to stick with reusing existing functions as much as possible instead of replicating their behaviour.

It is worth to note that for NSExceptions XCTest framework provides a richer API, which is unfortunately only available in Objective-C: https://developer.apple.com/documentation/xctest/nsexception_assertions?language=objc

Full documentation for all assert functions can be found here: https://developer.apple.com/documentation/xctest

Originally inspired by this: Tests that don’t crash by Erica Sadun.

Update for 2018

No new APIs have been added to XCTest since this article was originally published.

I have started looking into how I can contribute to the open-source implementation and created a pitch on Swift Forums. Do you want to help me with this? Reach out to me on Twitter, let’s make XCTest better together!

Thanks for reading. I hope you enjoyed the post 🙌

To get notified about new posts, follow me on Twitter or subscribe to the feed.

I also curate the best learnings from the community in a bi-weekly iOS Code Review newsletter 💌

This post is licensed under CC BY NC SA 4.0 by the author.